The fourth branch of government

We're cutting democracy out of our society's big decisions, and that's not a good thing.

After my recent argument that we need a NICE for SEND, I’ve been asked how this should be set up. Should it be a part of DfE? Should it be an independent agency? I started writing up my answer, but couldn’t do it without a diversion into political philosophy first. So here is the precursor - my theory on the fourth branch of government.

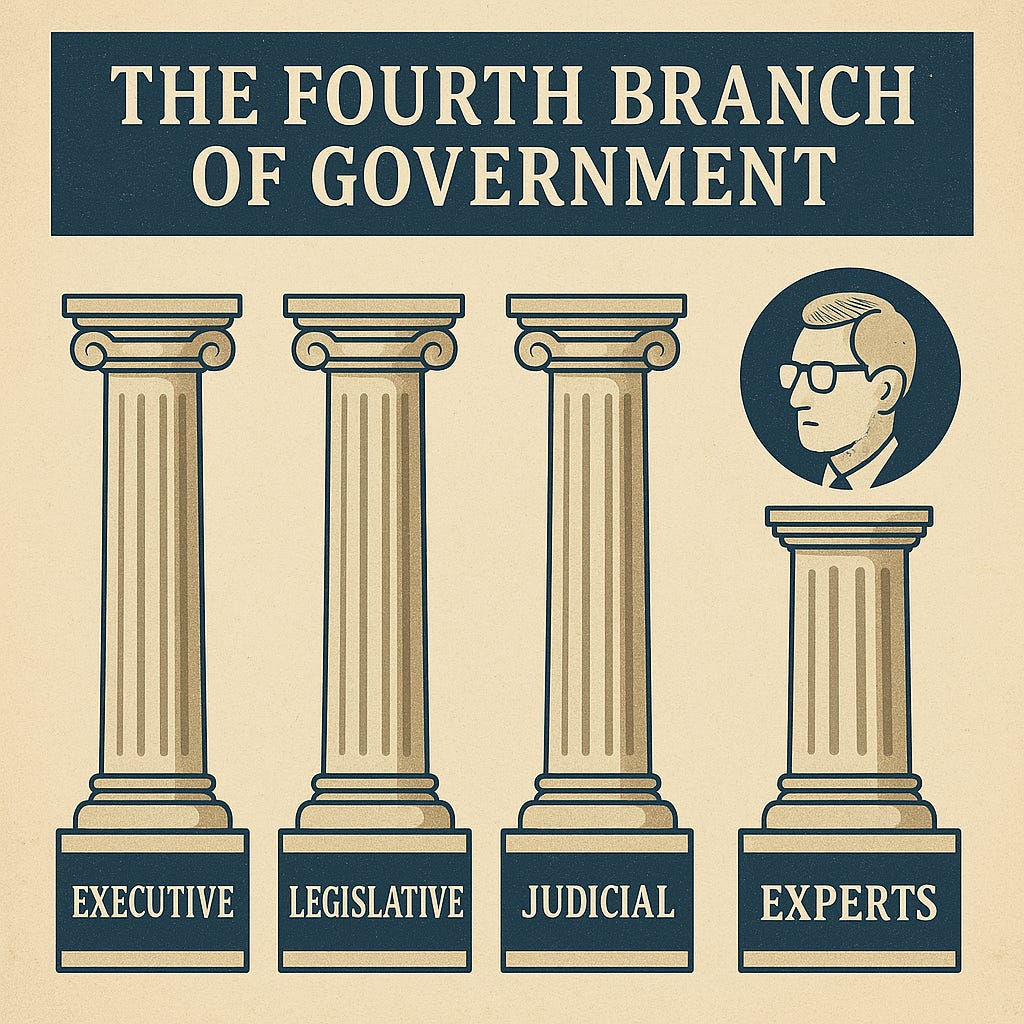

In Politics 101 you’re taught that government has three branches: the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. Once upon a time, this was true. But today, it isn’t. A fourth branch is well established - the expert branch of government.

In recent decades, we've witnessed the dramatic expansion of independent expert bodies - regulators, commissions, and agencies - that now wield powers previously reserved for politicians and judges. These bodies constitute a de facto fourth branch of government, one that derives its authority not from the people but from technical expertise.

As this branch has grown, the justification for its rise has changed. Originally the expert branch was needed because it brought technical knowledge that politicians lacked. Now it is needed because politics itself cannot be trusted. The rise of the expert branch isn’t just a reorganisation of how government works, but a fundamental change in how we conceive of a good democracy.

What is the expert branch?

In 2023 there were 304 arms length bodies across government. To give a sense of them, here’s the list of ALBs that are sponsored by the Department for Education:

Teaching Regulation Agency

Standards and Testing Agency

Office of the Children’s Commissioner

Oak National Academy

LocateED

Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education

Education and Skills Funding Agency

Ofqual

Student Loans Company

Office for Students

Ofsted

Social Work England

Engineering Construction Industry Training Board

Construction Industry Training Board

School Teachers’ Review Body

These are not homogenous organisations. Some are agencies carrying out delegated functions for the executive branch, like LocateED (who buy buildings to convert into schools) or the STA (who write and administer primary school tests).

Others do more than just implement government policy. They create new rules (a legislative function), interpret those rules and judge if they’re met (a judicial function), and enforce compliance (an executive function).

An organisation like Ofsted has quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial power. It sets a framework for what good education looks like (legislative) and judges whether this is met in specific cases (judicial). Crucially, it does this independently of the elected government, who must be consulted on Ofsted’s framework but cannot directly draft or amend it.

The same is true outside education. Natural England determine where roads can be built, the Competition and Markets Authority determine if companies can merge, the Climate Change Committee sets our carbon budget, UKRI decides who gets research funding, the Migration Advisory Committee decide which jobs go on the shortage occupation list, etc, etc.

These are not a few isolated agencies, but a full branch of government. Experts have traditionally been regarded as just a subset of the executive branch, but really their role - and their status outside of politics - puts them in a distinct category. They do not stand for election, yet they make decisions that have wide social and economic impact.

The expert branch of government, then, is the network of independent bodies that exercise significant power across traditional branch functions, and derive their legitimacy from technical expertise rather than democratic processes.

Input and output legitimacy

In political science, there is a distinction between political decisions deriving legitimacy from their inputs or their outputs.

Input legitimacy is when a decision derives legitimacy from how it is reached. For example, a decision made by Parliament has input legitimacy because the MPs who make it are democratically elected. Input legitimacy is independent of the actual decision - it’s legitimate because of the process, not because we like the outcome.

Output legitimacy is the opposite. It’s when a decision derives legitimacy from its results being high quality, regardless of any democratic input into the process.

Traditionally, the justification for granting power to the expert branch of government has been one of output legitimacy. The argument goes that for certain technical decisions - like setting interest rates, regulating nuclear energy, or maintaining water quality - expert bodies can produce better outcomes than politicians. Because politicians lack the knowledge to make informed decisions, experts make them instead.

This framework gives a neat distinction, albeit with a fuzzy boundary, about when to allocate decisions to the expert branch. Politicians have input legitimacy and should make decisions that depend on value judgements or big trade-offs. Experts have deep knowledge and should make technical decisions about how to achieve a clearly defined policy objective.

The problem is, this distinction isn’t being used in practice. The argument for handing power to the expert branch has transformed: it’s no longer just about output legitimacy (“experts make better technical decisions”) but has become a claim that input legitimacy doesn’t matter (“politicians can’t be trusted to make decisions”). The argument now runs that democracy, rather than conferring legitimacy, corrupts decision making.

We often see this argument in education. Organisations like FED argue that education policy should be made by an independent “Education Council” led by a Chief Education Officer, in order to take the politics out of education. I remember working at the DfE when the Chartered College of Teaching was being established. There were arguments to give away almost all the Department’s powers to the (then non-existent) College, from determining teacher qualifications to the curriculum to exam specifications. And with the government’s Curriculum and Assessment Review coming, we’re sure to see a wave of op-eds arguing that this should in future be decided by some independent body rather than the government of the day.

It’s the same in other areas. Politicians can’t be trusted with the environment, so give the power to Natural England instead. They can’t be trusted with climate change, so give the power to the Climate Change Committee. They can’t be trusted with migration rules, so give the power to the Migration Advisory Committee.

The anti-democratic consensus

This is a profound change in how we think about government. The original case for expert bodies - that politicians lack technical knowledge to achieve a policy objective - has mutated into something deeper. Electoral politics itself is now seen as the problem, and something to protect decision-making from.

There is the germ of a good argument here about the short-termism of politics. A politician’s main incentive is to win the next election, which means making the electorate happy at the particular moment they are heading to the ballot box.

This can cause problems in specific areas. Central bank independence is needed because of what economists call the time inconsistency problem. Governments want to boost the economy before elections, causing inflation. People know this, and so expect pre-election inflation. But these expectations themselves create inflation, even without government action. The best defence is to give monetary policy control to an independent central bank without strong political incentives. This means people don’t expect the pre-election inflation, which itself keeps inflation under control.

The success of central bank independence has led to arguments for similar policy-making independence in other areas of government. But the justification for independent monetary policy doesn’t work in most other areas. It depends on specific conditions - a clear objective (2.0% inflation target), well-understood tools for meeting it, and a time inconsistency problem where the mere expectation of poor political behaviour generates bad outcomes.

Most other policy areas don’t fit this model. Environment, curriculum, and migration policies involve value judgements and trade-offs that cannot be reduced to a single numerical target. None are analogous to the problem of inflation expectations themselves generating inflation.

When we hand over problems like these to non-democratic bodies we’re not solving a time inconsistency problem. We’re not optimising a technical solution for a well-defined challenge. We’re avoiding democratic debate about what we actually value.

The result is a gradual hollowing out of democratic governance, not because experts are seizing power, but because we're handing it over. We're convinced that democracy is the problem rather than the solution.

The illusion of the “right answer”

There’s a seductive belief at work here - that for every complex policy question there exists a single “right answer”, that experts can discover if only they’re insulated from politics. This technocratic fantasy has become our default mode of governance. As Keir Starmer said in a recent speech:

There is a knee jerk response to difficult questions, to difficult lobbies

The response goes like this, let’s create an agency…

Start a consultation…

Make it statutory, have a review

Until slowly, almost by stealth

Democratic accountability is swept under a regulatory carpet

Politicians almost not trusting themselves, outsourcing everything to different bodies because things have happened along the way – to the point you can’t get things done.

This proliferation of arms-length bodies has fractured our decision-making. Major societal choices are now made by people whose mandate requires them to ignore broader trade-offs in favour of optimising a single objective. And contrary to the technocratic ideal, these experts aren't immune to social pressure - they've merely substituted one audience (the public) for another (professional peers).

You can’t expertise away the hard choices

In politics, “There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.”

Part of the problem with the expert branch is that we have given bodies with narrow expertise the power to make broad decisions. A bat expert can assess the harm of building a road to the local bat population, but they cannot decide whether to build the road. For this you also need to consider the impact on people’s lives, on the local economy, on broader transport infrastructure. An ALB focused only on wildlife, but with the power to decide whether the road gets built, will make incorrect decisions because they are not considering all factors.

This is not about whether any particular ALB is doing a good or bad job, but that their job is itself problematic. Decisions should be made by people who are responsible for the entire outcome, not just a slice of it. Those people are politicians. They have to answer to the people for the overall quality of life in the country. They have to balance all the trade-offs and make a call. We can’t slice decisions up into neat little chunks and have them made by experts, because each expert never has to think about the whole.

Politics is hard because we need to weigh different considerations against each other and make a decision. The answers aren’t easy because politics is full of trade-offs. “To govern is to choose.”

Experts want people to like them too

The input legitimacy argument for experts is that politicians are too vulnerable to wanting to be liked, so they base decisions on what will win them approval rather than what is right. Unfortunately this is a feature of humans, not politicians, and experts are just as susceptible.

The difference is that politicians optimise for the opinion of the whole public, while experts optimise for the opinion of their peer group. One of the benefits of democracy is that a larger group is less susceptible to groupthink and bias than a small group. Expert groups are just as vulnerable to being overtaken by trends or blinded by convention as any other. There’s a reason “science advances one funeral at a time” (as Max Planck didn’t say).

Expert peer groups have gatekeepers who determine advancement and prestige. They have sacred beliefs upon which people have built careers and must not be challenged. They also have cultural and political biases determined by their most influential members.

All these factors affect how the expert branch of government makes decisions. The people working in these institutions need the approval of their peers to get jobs when they move on. They also have the simple human impulse of wanting to be liked by those around them. But unlike politicians, the people they want to please are a narrow subset of the population. This makes it more likely that niche beliefs, not shared by the people at large, can dominate and determine major decisions.

For example: Experts shouldn’t set the curriculum

I should love the idea that the school curriculum gets decided by experts. I’m a curriculum person who’s a former headteacher and has an OBE for services to education. In other words, I’m the sort of person who might well be part of any expert-led process to decide what gets taught.

People like me should be involved in setting the curriculum. We can advise on how to achieve a particular objective, or on the consequences of making a particular decision. But we have no greater ability to make trade-offs than non-experts. How does my expertise help me choose between the relative merits of teaching more languages over more arts? Whether to teach more plays or more poems? I can tell you how to improve a given type of outcome in a given area of maths. But which outcome to prioritise and which area? I have no greater right than anyone else to make that call.

The idea that a group of teachers would be less biased than politicians is also wrong. We have our own biases. We work in a small world where our career success depends on each other. If I want to get a job, to speak at a conference, or to sell a book, I need other teachers to like me. But teachers are not representative of the public - we’re graduates who are more socially and economically left-leaning. And we’re subject to terrible groupthink too - it was us who inflicted brain gym on a generation of children without an ounce of evidence it worked.

Big decisions like what to teach have to be made by politicians. They’re the only people who have to consider the whole picture and weigh all the trade-offs. They’re the only people who have to care about everyone’s opinion, not just a small sub-group. Experts can and should advise, but it shouldn’t be our call.

Where next?

Meaningful decisions in politics depend on making trade-offs. These trade-offs are, at their core, value judgements. And we make value judgements through democracy.

The expert branch of government operates with narrow remits but broad powers. It’s accountable to professional peers, not the public. This short-circuits democracy.

We have messy elections and political debates because they are the best way to reach societal value judgements. Outsourcing them to the expert branch might look cleaner and less dysfunctional, but it fails by pretending that decisions about what we value in life can be reduced to something simply technical.

Expertise can guide us, but it should not govern.

Lord Sumption has written at length about how we have a tendency to want to give more power to the judiciary, on the basis that law is a neutral, non-political way of making decisions.

Of course, putting a matter before a judge (or an ALB) does not make it any less political. In ‘The Political Constitution’ (1979), J.A.G. Griffith puts the matter pithily in relation to Article 10 of the ECHR (which at the time was not incorporated into domestic law):

> [Article 10] follows the pattern of many of the other Articles. It begins with general statements of principle and then adds a series of exceptions. Article 10 reads:

> “1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

> “2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.”

> That sounds like the statement of a political conflict pretending to be a resolution of it.

Ultimately, politics is the art of the peaceful resolution of trade-offs. Handing those trade-offs over to somebody else does not make them any less political.