The word crisis is over-used in public policy. We’re desensitised to hearing it, and it has lost all shock value. But the SEND system is in crisis, and we should be shocked.

School leaders are struggling to manage the huge demands this broken system places on them. Local authorities are only avoiding bankruptcy because the government have declared that their SEND deficits don’t count. Parents are enduring years-long battles to get even basic support for their children. And children, our children, are left without the education and care they deserve.

I know enough stories of real children whose lives have been irreparably harmed by this crisis that thinking about them for long enough to write this sentence brings a literal tear to my eye. It is not okay.

A broken system, circa 2014

If this were a crisis caused by demographics or external factors it would be bad. But although those things have an impact, they are not the cause. The truth is that this is a crisis of our own choosing.

Tom Rees, the Chair of the government’s new External Advisory Group on SEND, said this in a speech last week:

“The 2014 reforms, which we had a lot of hope and optimism about, have made things worse. We should be honest about this and say ‘the system isn’t working because it’s a bad system’ and not dance around that and pretend that it’s because schools haven’t done it well enough, because we need more funding, or because it’s the fault of parents or worse still, children and young people.”

The system isn’t working because it’s a bad system. And it started in 2014.

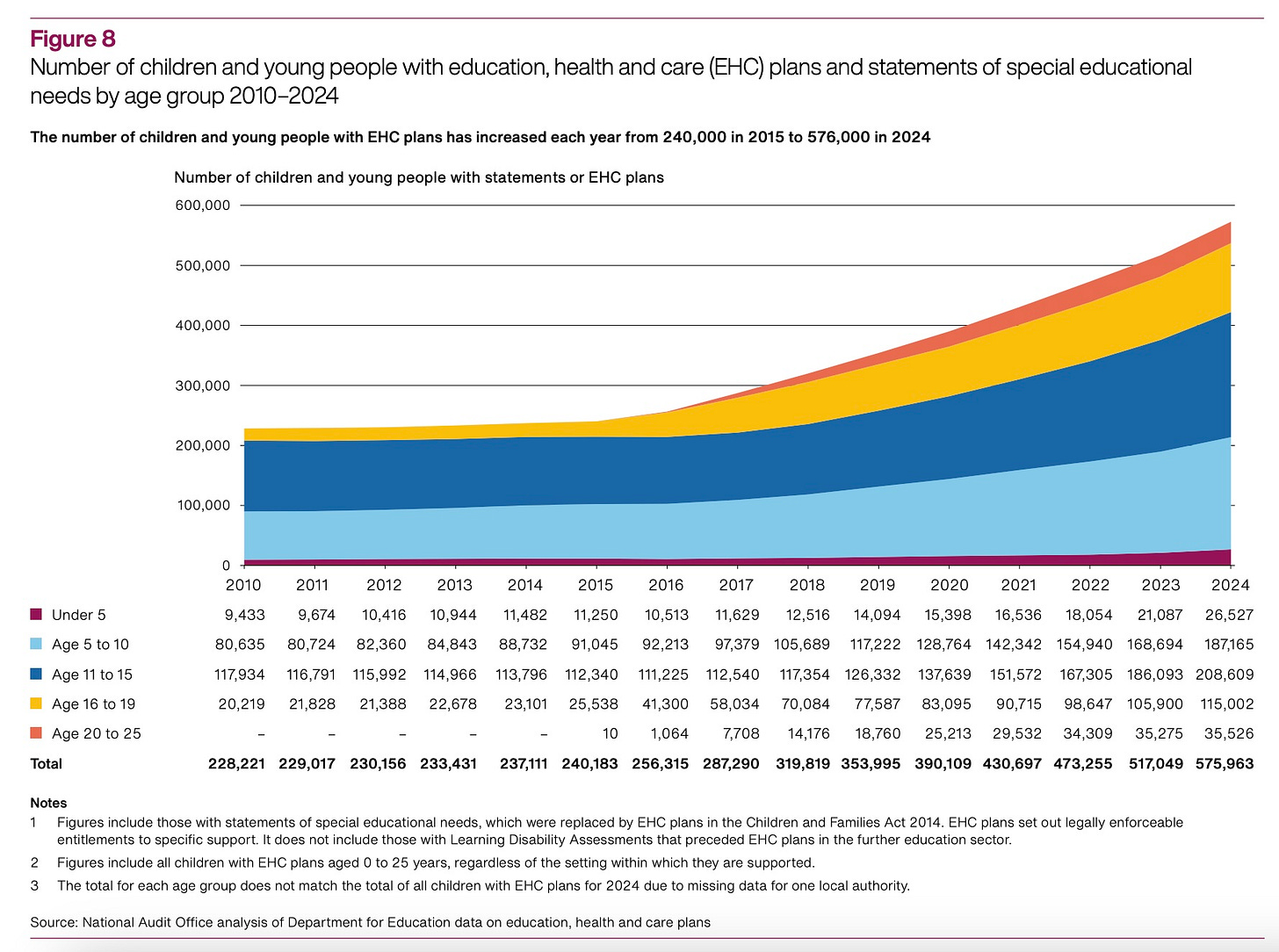

In 2014 the coalition government introduced the Children and Families Act. This replaced the previous system of statements with education, health and care plans. The chart below shows what happened.

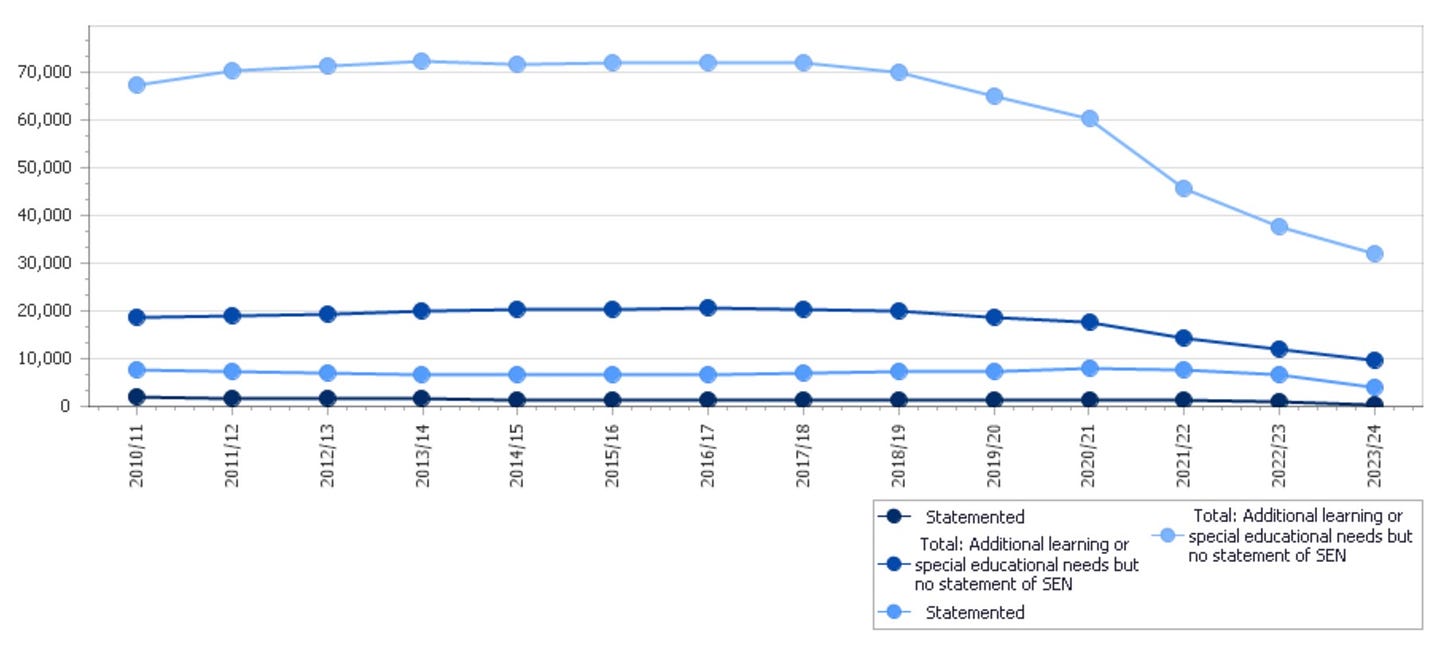

We have a control group for these reforms, which is Wales. Wales had the same statement system as England prior to the 2014 reforms, and kept the system up until reforms a couple of years ago.

If there were some outside non-policy factor dramatically driving up SEND rates we’d expect to see it in Wales too. But we don’t, because the problem is the system we chose to create.

The vicious cycle

In a world of struggling public services, especially child and adolescent healthcare, we have created a system that gives a small group of children a legal entitlement to specific care. The EHCP gives you, a named individual, a legal right to receive immediate specified support from the state. This means that the state must give you that support before it can give support to others.

This is often characterised as a system where parents chase a golden ticket for their child. But I think this is wrong. It’s more that parents are avoiding being left ticket-less. They know that if they are left in the group without an EHCP then there won’t be enough resource left to go around.

But of course this makes the pot of resource for early support ever smaller, further reducing the threshold at which one is at risk from not having an EHCP. Children who would once just have got the help they needed, now need an EHCP to secure that entitlement.

Because EHCPs determine funding, schools are incentivised for inclusion not working. If a school can show that a pupil isn’t succeeding at school then they get extra resource, whereas if they can support the pupil successfully then they don’t. This is a perverse incentive that rewards the opposite behaviour to the one we want! Many schools fight these incentives, but they are having to do the opposite of what the system is encouraging.

All this is taking place in a context where there is no independent reference point for what good support for a child looks like. In health we are very clear what good diagnosis and support looks like, as NICE prepare and publish detailed condition-by-condition guidance. If you are going into a hospital you can print out the relevant NICE guidance and know what support you should receive. We have no such equivalent in SEND.

The lack of external reference exacerbates the problem above. Nervous parents do not know what the right support for their child is, and understandably want to err on the side of too much than too little. They also don’t have a way to differentiate between what support is evidence-based and what is speculative. Constrained local authorities have an incentive to minimise cost, and don’t have a clear standard for what they should be providing.

The result is a kind of trial by combat, where parents and local authorities are forced to fight to determine what support their children get. This isn’t their fault. The system is broken because it’s a bad system. We shouldn’t put either parents or LAs in this position.

What are special needs anyway?

The 2014 Children and Families Act says:

“A child or young person has special educational needs if he or she has a learning difficulty or disability which calls for special educational provision to be made for him or her”.

This definition is circular - and this is the core of the problem. We have a medical model of SEND that restricts support to children who have a SEND diagnosis or label, like this is an inherent property of that child. But all SEND means is that the child needs extra support. Why do we force so many children through this arduous process of obtaining a SEND label in order to get the support they need, when all the SEND label tells us is that they need support?

Our language around this shows how problematic it is. We talk about ‘diagnosing’ SEND. But what does it even mean to get a diagnosis of needing extra help? Or worse, we talk about whether or not a child “is a SEND pupil”. We ask “are they SEND?”. How awful.

Tom’s speech quotes Nicole Dempsey, a brilliant leader at Dixons, who argues that “There are not children and SEND children. There are just children.”. Children who vary in their levels of development. Children who face differing challenges in their lives. Children who have different medical needs.

Why should the child who gets an SEMH diagnosis go into a special school, whilst their diagnosis-free peer gets permanently excluded and given a seat at online school or two afternoons a week in a portakabin? Why should the child with an old SLCN diagnosis get statutory entitlement to reading support, whilst their friend who’s just four years behind their chronological reading age gets nothing? Why can’t we see children as children, and give them the support they need?

This is emphatically not an argument for reducing support or denying children’s needs. It is an argument that for no child is their requirement for extra support in education the defining feature of their identity. An argument that children should not need to be classified by the bureaucracy, at massive cost, in order to be supported through their childhood.

A better future

We should be striving towards a future where we are clear on what great support looks like for children who need it, across domains and levels of development. This support should be available with minimal hurdles. Of course there are some expensive and scarce resources where we will always need a gateway or process, like admission into special schools. But children should not need to be labelled by a bureaucrat in order to receive the support that a basically functioning education system should just be able to provide.

___

I’m due on paternity leave soon, but when children allow I will write a part two on how we might build this future.

Superb piece - chimes with IFS work: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/spending-special-educational-needs-england-something-has-change

I think this is a good articulation of they key challenge - and one that was complete heresy in the DfE a few years ago. I do think we could be further on our way to addressing some of this than we acknowledge. The evidence base on SEMH and SLCN is really strong! There’s loads of what works level evidence on how you can improve communication and language skills, improving social and emotional regulation, improving mental health outcomes. If we started with these needs and provided funding and guidance to improve practice, we could make a transformative difference more quickly than we think.