There's nothing middle class about learning

Their motives were various, but their primary objective was intellectual independence… There is nothing distinctively “bourgeois” in this desire for intellectual freedom.

The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, Jonathan Rose

I

Average attainment in England is now much higher than it was a few decades ago. But as always, the average masks a distribution. And at the bottom of that distribution are white British working class children.

FFT Education Datalab recently crunched the numbers, and it’s horrifying. The GCSE pass rates of white FSM boys is less than half that of non-white non-FSM girls. Less than half. And it’s this bad whichever measure you look at. Their attendance is worse, they’re more likely to be excluded, they make less progress.

The most shocking stat to me is that over 50% of white working class boys are diagnosed with SEND at some point during their time at school. How have we reached a place where over half of these children are formally classed as being unable to access education without extra support? These are children with deep roots in this country, from families with long traditions of work and responsibility. We cannot possibly believe that the prevalence of cognitive or medical barriers to learning for these children is over 50%. Something else must be going wrong.

It is striking that whatever is going wrong for white working class children is going right for children whose parents immigrated to Britain. In the last PISA round the highest-attaining children in England were second generation immigrants - and we were the only developed country where this was the case. This is like how the famous “London effect” of school improvement largely disappears when you control for ethnicity.

Broadly speaking, two groups of children do well in our system: white middle class children and children of immigrants. I think the explanation for this is simple. At some point the purpose of our school system became confused. Instead of being designed to pass on knowledge, it became designed to make you middle class.

This is good for white British middle class children - it makes them feelscomfortable and highly values the attributes they associate with their home and family. It also works well for children of immigrants - they want to climb the socio-economic ladder in their new home country. White working class children are less comfortable, because the signal we send is that the purpose of school is to make you not like you.

II

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this system was built in the early 2000s. This was “end of history” time, “no more boom and bust” time, “everyone will work in service industries and be rich” time. The future of this generation was to get degrees, become lawyers or HR professionals, and be comfortably middle class forever.

We said that schools were just about learning. That the purpose of education was the enriching of the intellect. But this wasn’t true. We confused education of the intellect with preparation for middle class service sector jobs.

We began caring more about the qualifications that get you on the next rung of the ladder towards middle-classness than we did about what you actually learned. We began caring as much whether you looked middle class when at school as about what you actually learned.

Like every teacher I’ve had plenty of conversations where a pupil or parent challenges uniform expectations with a version of: “but how does this affect my learning”. I’m not justifying this - communities are built on shared norms and schools need to uphold them. But there is a grain of something to this response. Why is it that we’ve chosen to make dressing in suits such a big signal of whether a school is good? Why is it that the first thing leaders do when trying to improve a school is to make the norms of dress more middle class?

I remember visiting Dixons Trinity Academy, one of the best schools in the country, and hearing the founding Principal talk about uniform. At DTA children wear polo shirts and hoodies. Luke talked about how they let children choose what colour they’d like to wear because having some autonomy is important for motivation. If children didn’t feel some autonomy in school then it would be harder to motivate them, and as there was little autonomy in what they learned it made sense to give it in something that doesn’t matter for learning - like polo shirt colour.

I pick on uniform because it is an example of a well-intentioned heuristic that has gone too far. Many of us, full of ambition for working class children, have looked at private schools and said “why can’t our children get an education like this”? But too often we’ve copied the surface features rather than the deep ones. We’ve focused on making our children look like they go to private school rather than relentlessly working to ensure they learn as much as the children that do.

This conflation of learning with becoming middle class is a novel phenomenon. There is a proud history of working class intellectualism in this country. Our collieries had libraries and reading rooms. Our working men sang classical music in choirs. I live round the corner from David Parr House, where a working class man turned his terraced house into one of the most stunning examples of Arts and Craft Movement design anywhere in the country.

The Wizard of Waverley had roused the world to wonders, and we wondered too. Byron was flinging around the terrible and beautiful words of a distracted greatness. Moore was doing all he could for love-sick boys and girls,-yet they had never enough! …

Oh! how they did ring above the rattling of a hundred shuttles! Let me again proclaim the debt we owe those Song Spirits, as they walked in melody from loom to loom.Rhymes and Recollections of a Hand-Loom Weaver, William Thom

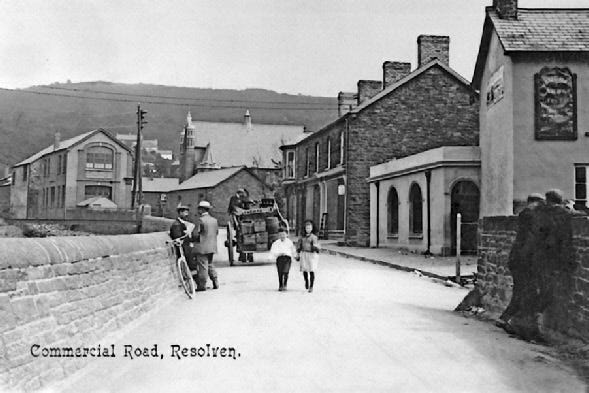

The oldest books I own are cherished bibles, passed down through generations of Welsh miners. When I got into Oxford my grandfather proudly told me about his time spent studying at Keble College, on an engineering course for miners. He never believed that intellectualism belonged more to the middle classes than to the working people of Resolven.

The weavers and miners who wrote poems and inhabited reading rooms did so for their intellects. They believed that the knowledge and literature of Britain was theirs. They didn’t feel the need to change how they dressed or behaved in order to exercise their minds. They were working class and they were intellectuals - this was no contradiction.

III

Years ago I went on a trip to Boston, MA to visit a set of local charter schools. The thing that struck me most was the deep sense of purpose shared by these schools and the children in them. In some cases it was explicit, in others implicit, but in all it was palpable. These institutions existed to right the historic wrongs of racism that had held back these children’s parents.

I’ve thought ever since about what the equivalent mission of our schools is for our working class children. I fear that in too many cases it is, implicitly but unmistakably, to ‘rescue’ children from their upbringing and make them ‘better’ than their parents.

I don’t mean this in terms of learning. All schools aspire that children should learn more than the previous generation, and all parents share this aspiration. I mean it in terms of culture and norms. We’ve decided that learning must be paired with middle class norms, and so in order to access knowledge working class children need to change.

No wonder this doesn’t work. We can’t motivate a generation by telling them that their parents are the problem, that their communities are the problem, that to succeed they need to leave their people behind. It should not surprise us that families are en masse revolting against this message.

Our message to children needs to change. The knowledge in our schools is theirs. It is their birthright. It is not being forced upon them because of a failing in them or their parents. It is being passed on to them because they have a right to it. They are not poor children from inadequate families who need saving. They are children from families we respect, upon whom we are conferring a hard won and joyful inheritance.

I couldn't agree more; and also agree that this is a relatively new conception. I think it links in to the 'means to an end' view of education - if you think this is only important because it leads to a job that isn't for you, why bother?

Back in the early 1900s Charlotte Mason worked in schools for children in mining villages from illiterate families and had them reading the classics, memorising poetry and studying art to "hang permanently in their imagination", because "a liberal education is, like justice, religion, liberty, fresh air, the natural birthright of every child." Somehow it feels that within a focus on disadvantage we have given the impression that this is not natural and has to be forced rather than offered.

A huge amount to think about here - thank you